Identifying Influence in Geopolitics: China’s Belt and Road Initiative

By: Thomas Scherer | October 24, 2023

Secretary-General António Guterres addresses the Belt and Road Initiative Forum on International Cooperation, in Beijing. UN Photo/Zhao Yun

Among China’s economic coercion efforts for influence, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s $1 trillion (and growing) infrastructure investment program. U.S. policymakers are concerned that China is gaining influence over countries that have received BRI funding. At a June congressional hearing on Assessing U.S. Efforts to Counter China’s Coercive Belt and Road Diplomacy, Rep. Michael McCaul warned, “China’s malign influence is growing exponentially, and its encroachment into the Western Hemisphere poses a clear and present danger.” A Council of Foreign Relations Task Force found that the BRI made “countries more susceptible to Chinese political pressure while giving China a greater ability to project its power more widely.” To counter that growing influence, the G-7 launched a $600 billion Partnership for Global Influence, with $200 billion coming from the United States.

There’s a big assumption baked into this financial arms race to exert influence: More investment causes more influence. But is that even true? Before (or while) spending so much to counter China’s BRI, the United States should be asking what influence exactly China is gaining. The answer might seem obvious, but that is precisely when cognitive bias can blindside us the hardest. It's better to be sure before making a $200 billion bet.

In an era of multilateral competition and a large number of high-stakes challenges where U.S. dominance is no longer a given; the United States must improve its decision-making process, and that requires testing assumptions. The margin for error in our foreign policy grows tighter by the day, and our institutions must up their game.

Unfortunately, our foreign policy processes are not built to challenge assumptions and mitigate biases. A prominent example comes to mind: in the Syria crisis, CIA Director David Petraeus presented a plan supported by Secretaries Panetta and Clinton to arm Syrian rebels without reviewing whether such plans worked in the past. Only after President Obama requested that information did the CIA check the historical record, finding that such plans rarely achieve their goals.

When fp21 advocates for more measurement in foreign policy to empower decision-makers with better information and evidence, a typical retort is that such efforts are unnecessary – that our intuition is superior. New research demonstrates why it can be so powerful to challenge our assumptions with careful measurement strategies.

What do we really mean by “influence”?

New research from Yining Sun, Ethan Kapstein, and Jacob Shapiro demonstrates that with regards to the BRI, once again, we should always test our assumptions. They find local politicians whose districts win big development projects from China through the BRI display virtually no increased support for China. If the BRI is, at least in part, intended to win the hearts and minds of the local populations, it may be failing.

The researchers theorize that if the BRI is gaining goodwill for China, we should observe increased goodwill in the social media posts of local politicians in districts that receive BRI projects.

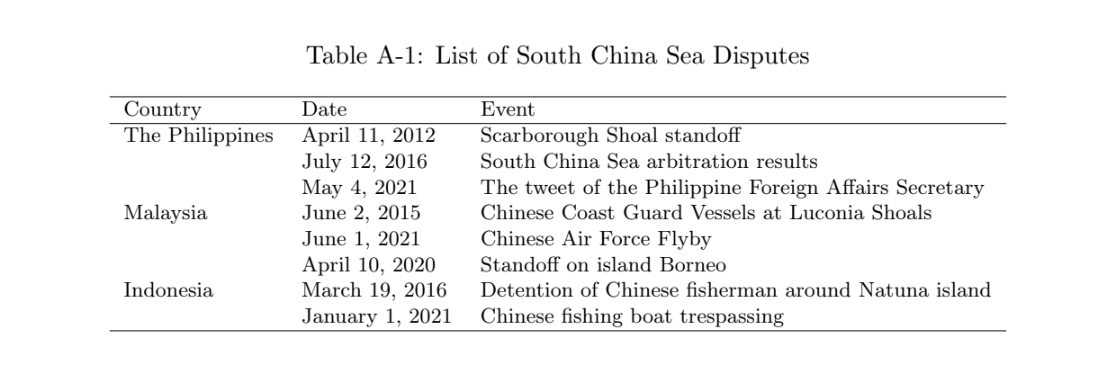

Using cutting-edge computational social science, they find little evidence to support this hypothesis. The team collected some 180,000 posts about China from over 3,000 local politicians from Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines and measured their sentiment (see examples). They then confirmed the geolocations of 130 BRI projects to determine whether each politician benefitted. Finally, to identify periods where all politicians should be paying attention to China for the same reason, they identified major events in each country’s dispute with China over the South China Sea.

Figures from Online Appendix of Sun, Yining, et. al. (2023)

As we know, correlation is not causation. A “naive” strategy would be to simply track the change in sentiment in target countries following investments. But simply witnessing increased positive sentiment about China is insufficient. To show that the goodwill is caused by the BRI investments, one needs to compare “treated” vs “controlled” leaders. If positive sentiment increased among BRI recipients but not non-recipients, causation is plausible.

But no such proof is found. There is no significant difference in the number or sentiment of posts about China between politicians of districts that received BRI support and those that did not. There is one exception: Malaysian politicians in BRI districts are friendlier for about seven days in their Facebook posts (but not in their tweets).

This research alone does not mean that the BRI does not have other effects or that the Partnership for Global Initiative is unhelpful. Social media sentiment is only one of many ways of measuring the impact of the BRI. Nevertheless, as policymakers are prioritizing goals and weighing the tradeoffs of different policies, they should have all the relevant information, which now includes this high-quality evidence that China is not winning hearts and minds through the BRI.

Conclusion: It is irresponsible to leave assumptions untested

This research highlights the feasibility and importance of testing our foreign policy assumptions. Before (or while) designing policies to prevent China from gaining influence through the BRI, the United States should be asking how exactly it is gaining influence and how we can measure it. Similarly, we need to be measuring the effectiveness of U.S. policies: if BRI is not working as we’d expect, will the Partnership for Global Influence?

We should recognize that this type of research requires time and resources — investments the State Department typically does not prioritize. The above mentioned research was supported by a grant from the Department of Defense through their Minerva Research Initiative. Such investments in research the organization better understand the world. In this case, the research not only answers a key policy question relevant to a $200 billion investment, it also provides a model for how to measure foreign influence through local social media, a handy tool to add to the multi-method toolkit.

Unfortunately, where other government agencies fund research directly or through FFRDCs (federally funded research and development centers), the State Department currently lacks similar mechanisms to fund relevant research. Such efforts are vital to improve the quality of US foreign policy.