How to Make Rubio’s State Department Reform a Success

By: Dan Spokojny | April 29, 2025

According to some of the State Department’s staunchest defenders, the Trump Administration’s reorganization plan for Foggy Bottom is deeply troubling. The Department, critics argue, has long suffered from insufficient resources and authority. With more budget and staff cuts on the horizon, in conjunction with a weakening of protections for career public service, many commentators sense a dangerous moment for American diplomacy.

But I have been critical of our leaders, especially career diplomats, for resisting real reform at the State Department under previous administrations. Between the marginalization of career diplomats, a culture that fails to learn, and an outdated policy process, the necessity for reform has been loud and clear.

I don’t know what the future holds, and it is hard to write about reform while so many people risk losing their jobs. Nevertheless, I want to explore the argument that Secretary of State Rubio’s reorganization plan may lead American diplomacy to a better place. This is a pivotal moment for American foreign policy, and advocates for diplomacy need to join the conversation about reform and help lead this institution to a stronger footing.

Rubio’s Theory of Success?

Rubio’s explanation for cutting bureaus and offices at the State Department centers on efficiency: leaner is better. Eliminating redundancy and cutting the fat, according to this theory, will lead to better policy.

The cynical analysis of Rubio’s plan is that top officials always believe their own policy ideas are brilliant; the bureaucracy just needs to get out of their way. Everyone else’s office is too large and powerful, but one’s own office never has enough resources or authority. If this cynical perspective is right, Rubio’s plan is less about efficiency and more about the consolidation of power at the expense of good foreign policy.

And yet, one can find support for the “streamline” theory espoused by Democrats and career diplomats. Uzra Zeya and Jon Finer, two prominent Obama and Biden administration officials, offered a similar analysis in a 2020 report:

Multiple undersecretaries or their staffs should not be involved on the same policy issues. Reducing the number of undersecretaries, with bureaus allocated underneath them at the discretion of the incoming secretary of state, would help eliminate overlapping responsibilities, empower assistant secretaries and equivalents (such as the counselor and director of policy planning), and reduce layering while leaving sufficient senior management capacity in place.

Three luminary career ambassadors working at Harvard’s American Diplomacy Project similarly called for:

Systematic efforts … to devolve responsibility to the lowest possible levels, including a dramatic streamlining of clearance processes and a flattened organizational structure with fewer bureaus and enforceable limits on the number of Deputy Assistant Secretaries.

I thus think there is plenty of reason to evaluate Rubio’s plan in an optimistic light.

Strengthening Regional Bureaus

The most compelling theory of success for Rubio’s reorg is that a transfer of power to the regional bureaus will not simply streamline, but also encourage increased cooperation within the Department. Let me explain.

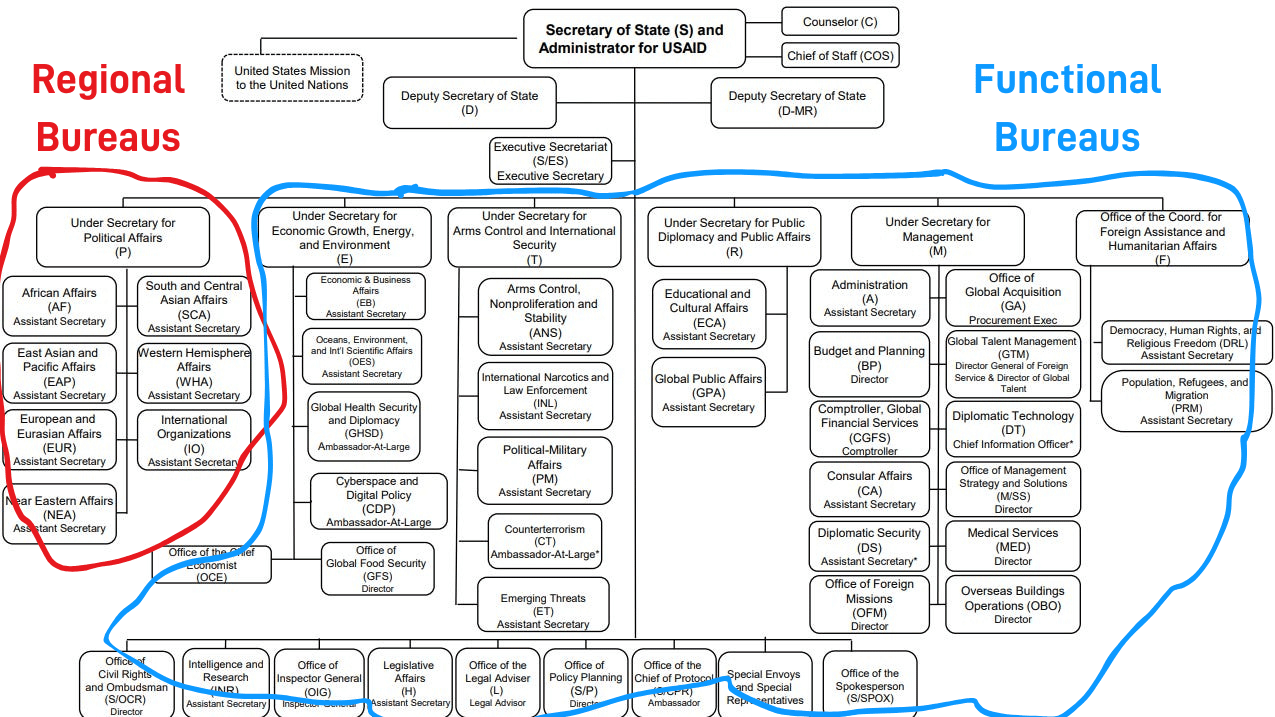

One of the State Department’s core organizational design features is the division between regional and functional bureaus (diagramed below). The regional bureaus, organized under the powerful Under Secretary for Political Affairs, own the bilateral relationships with foreign countries. They control policy through their management of the embassies and other diplomatic missions. The functional bureaus, organized under a variety of other undersecretaries, are responsible for cross-cutting, transnational issues. Functional bureaus are typically dependent on the consent of regional bureaus to implement policies in any particular country.

Rubio’s updated organizational chart, 4/24/2025

If one compares this new org chart with the old one, one finds that it closes or consolidates many of functional bureaus (including the largest functional undersecretariat formerly known as J), resulting in a transfer of authority to the regional bureaus. This change may have a meaningful impact on the design of foreign policy.

The logic of the functional bureaus is that some topics in foreign policy, like human rights, anti-narcotics, or nuclear proliferation, are so important that they require independent offices with specialized expertise. Under secretary and assistant secretary-level leadership of these issues helps ensure that the issues will always have a loud voice, a powerful advocate, and a bevy of technical expertise. For example, creating a powerful office of human rights office will ensure human rights are never ignored. Right?

Not so fast. The establishment of issue-specific offices does not necessarily lead to better policy. It may only introduce new turf battles. I witnessed this firsthand when I worked in the Conflict and Stabilization Operations Bureau (CSO). The bureau had a great deal of knowledge, but it was constantly fighting for relevance with regional bureaus. It is not as if one becomes the Ambassador to Syria, or somewhere similar, by being ignorant of regional conflict dynamics. As a result, CSO’s impact on conflict policy was limited, at best.

When one imagines a corporation creating a distinct operational unit, one imagines that those uniques produce a distinct output: product design, manufacturing, sales, human resources, etc. The State Department's regional versus functional design seems to violate this organizational design principle. Whereas a regional bureau creates policy for the countries in its purview, the human rights bureau also tries to make policy for those same countries (and, in fact, has an internal office structure that replicates the regional bureau model on a smaller scale, dividing up the world according to region). It would be wrong to suggest the Assistant Secretary for Near Eastern Affairs is ignorant about human rights issues – quite the opposite. Their job is to balance human rights, conflict management, economic, security, and a million other concerns.

The amount of overlap between regional and functional offices varies depending on the issue areas. It makes a lot of sense to exclude from the purview of regional bureaus offices with specialized roles like Diplomatic Security, Legal Affairs, Consular Affairs, and Legislative Affairs. The arms control bureau certainly overlaps regional bureau territory, but it employs nuclear engineers with technical expertise that is inaccessible to typical foreign affairs officials — the case for an independent arms control bureau thus seems reasonable. Can one argue that human rights, conflict stabilization, refugees, or counter terrorism require specialized, technical expertise? The arguments here are less strong.

In sum, Rubio’s plan to pare back the functional bureau model is logical. The State Department has a bad habit of setting up a new office for every new slice of foreign policy. The result is a great deal of competition and turfsmanship, leading to a bureaucracy that often seems duplicative, ineffective, and wasteful. Arduous consensus procedures lead to watered-down and risk-averse conclusions.

Rubio’s reorganization plan will challenge this logic by doubling down on the centrality of the regional bureaus. Will it work? Who knows. But fulfilling the promise of this theory won’t happen automatically. It will require some additional steps.

The Path Towards Effective Reform

If Rubio’s reorganization is to be a success, it will need to help facilitate a more cooperative and collaborative policy environment. There are a variety of steps his team should consider:

Rubio’s team should hack the incentive structures that lead to turf battles by designing new mechanisms that reward coordination between bureaus. This might entail designing a more evidence-based decision-making process to replace the outdated clearance process. Further, investments in enterprise knowledge management can combat information siloing, a telltale sign of turf competition.

Strengthening the strategy and budget process may be the best opportunity for Rubio to create a more effective and efficient Department. Procedures for central planning at the State Department are currently weak and ineffective, and regional and functional families have separate strategy processes. This creates barriers for cooperation, resulting in a muddled strategic landscape that attempts to make every issue a priority, even when goals may work at cross purposes. Introducing a new doctrine for policy engineering would support more effective action to achieve US national security goals.

The promotion process for Foreign Service Officers also deserves attention. The current process encourages a “kissing up and kicking down” mindset that encourages loyalty to one’s direct manager. There is no structural reward for collaboration outside of one’s stovepipe. Because of this, an officer serving overseas will typically be more responsive to the regional bureau that owns their turf while deprioritizing requests from functional bureaus who have no input into their promotion review. A more robust merit evaluation system would hold officials accountable for the achievement of both regional and functional bureau goals.

With regional bureaus being asked to take more responsibility and management of foreign assistance projects in the aftermath of the USAID closure, many foreign assistance professionals worry that these offices lack the skills to manage and support programs. They are right to be concerned. Program management entails a variety of technical skills, including budgeting, design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, grant and contract management. Regional bureaus, primarily staffed by Foreign Service Officers, tend to lack these skills. Rubio might require that all Foreign Service officers receive program management training. These skills are quite useful for policy design and strategy as well, which would be a boon for the Department.

Updated Organization Requires Updated Culture

The shuttering of dozens of functional bureaus and offices means that regional bureaus will have to shoulder more responsibility for integrating diverse expertise into the policy process. To make this change stick, Rubio must challenge the top-down decision-making culture at the State Department. As the world grows ever more complex, our leaders must relinquish the expectation that they can know everything.

Consider US strategy toward Russia. An effective strategy will require expertise not only on Russian politics, but also the war in Ukraine, fiscal and trade policy, military capabilities, tech competition, energy issues, human rights and democratization, regional alliances like North Korea and China, cybersecurity, and so much more. No one top decision-maker can understand the complexities of each of these issues. Instead, leaders in a streamlined Department will need to demonstrate deep respect and curiosity for their working-level experts. They need to learn to draw together teams with divergent specializations to design carefully calibrated policies.

Ultimately, the State Department boasts expertise on a dizzying array of issues. A weak Department allows those many different teams to compete for attention and resources, expending precious time and energy on bureaucratic battles, resulting in risk-averse policies that impress nobody. A stronger Department will create synergy and cohesion among its many actors. I hope Rubio has the vision and skill to build a stronger, more effective, and more efficient Department.